Breaking down the complex array of factors that shifted our nation’s meat supply seemingly overnight, sending livestock markets and food prices, alike, into convulsions.

By Michael Nepveux, American Farm Bureau Federation economist

The self-distancing and quarantine protocols put in place to slow the spread of COVID-19 reduced economic growth, kept consumers in their homes and changed the way Americans purchase and consume food.

Food production, too, was significantly disrupted, especially at livestock processing facilities, where labor shortages and worker protection measures slowed throughput at plants around the country and even caused some facilities to shut down.

While we certainly are not over the COVID-19-induced disruptions to the economy, our food supply chain has largely adapted to continue to provide food for the country, although agricultural producers continue to feel extreme pain.

In many ways, COVID-19 has helped many Americans gain a better understanding of who grows their food and how it gets from the farm to their tables.

Food consumption in America

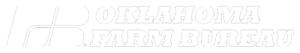

Before the pandemic, consumers in this country were spending more of their food dollars than ever before away from home.

Statistics from USDA’s Economic Research Service show consumers spent a record $1.7 trillion on food and beverages in 2018, up $78 billion, or nearly 5%, from the previous year. Of that total, food purchases in grocery stores, warehouse stores or supercenters totaled $628 billion, up $23 billion, or nearly 3%, from 2017.

Food purchases in full-service and limited-service restaurants totaled $678 billion – $50 billion more than sales in grocery-type outlets and up $39 billion, or nearly 6%, from the previous year. Food purchases in restaurants have exceeded those of grocery-type outlets every year since 2015.

Figure 1 (below) shows consumers’ dramatic response to shelter-in-place orders and dine-in restaurant closures, with the amount of money spent at food service establishments declining drastically in April. This shift had far-reaching implications that rippled through the supply chain all the way to our nation’s farmers and ranchers.

Many products going through the food service demand channel are prepared or packaged in a specific way, and shifting this product from ood service to retail is not a logistically simple task. One of the main challenges is that processors, who may produce curated proportioned product or specific packaging for a particular restaurant, may not be able to immediately produce case-ready meat for the grocery store.

Pressures on the supply side of the equation

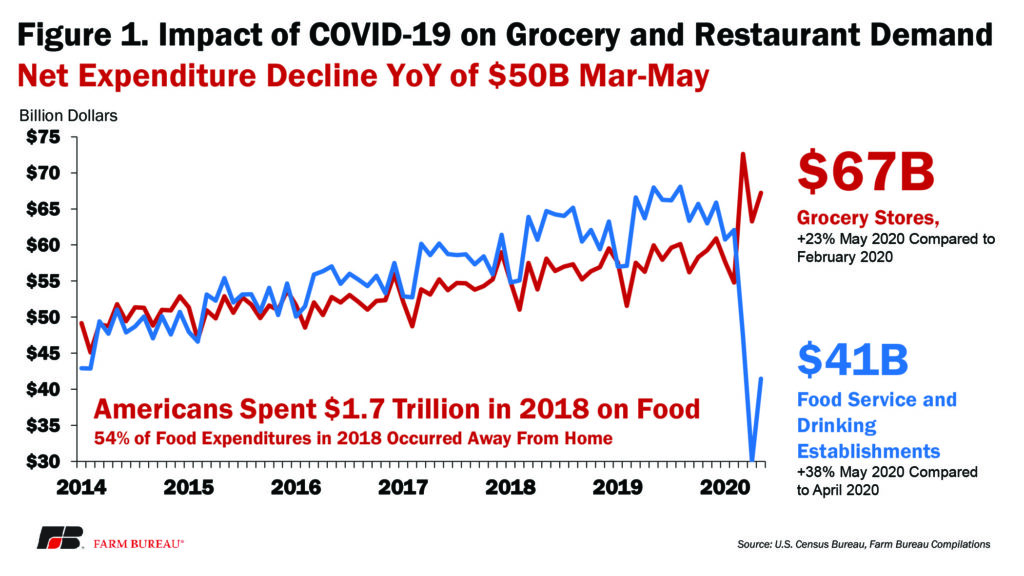

Ranging from a few days to two weeks, over the past several months, dozens of livestock processing plants closed temporarily due to issues with COVID-19. In some cases, the closures were due to outbreaks among workers at the plants. In other cases, it was a struggle to keep workers, who were afraid of getting sick, coming into the plant.

Given that these facilities closed and reopened at irregular intervals, estimating impacts to the country’s processing capacity is difficult.

However, we can estimate that at times over the previous few months, pork processing capacity was reduced by as much as 20% due to plant closures and beef processing capacity had been reduced by as much as 10%.

These estimates were derived from publicly available information and company announcements about packing plants and further processing facility closures. They do not factor in reductions in capacity due to slowing throughput and reduced line speeds at these facilities, which also reduce capacity.

In an effort to protect employees, processing companies implemented new policies (such as installing Plexiglas barriers between workers, spacing employees further apart, etc.) and incorporated more social distancing in their facilities, which slowed the flow of product through their lines.

This reduction is more difficult to quantify but has the potential to have more far-reaching impacts than direct plant closures. One data point that we can use as a proxy for this difficult-to-gauge number is overall weekly slaughter of cattle and hogs.

Figure 2 (below top) shows the drastic drop in slaughter numbers for hogs and cattle. At its worst, weekly total cattle slaughter decreased by 35% from 2019, but since then it has largely recovered.

Weekly hog slaughter dropped 35% from 2019, but has already recovered to levels above last year’s. It took over a month, but for the most part, slaughter capacity has largely returned to “normal” and is above 2019 levels, if not quite to early 2020 levels.

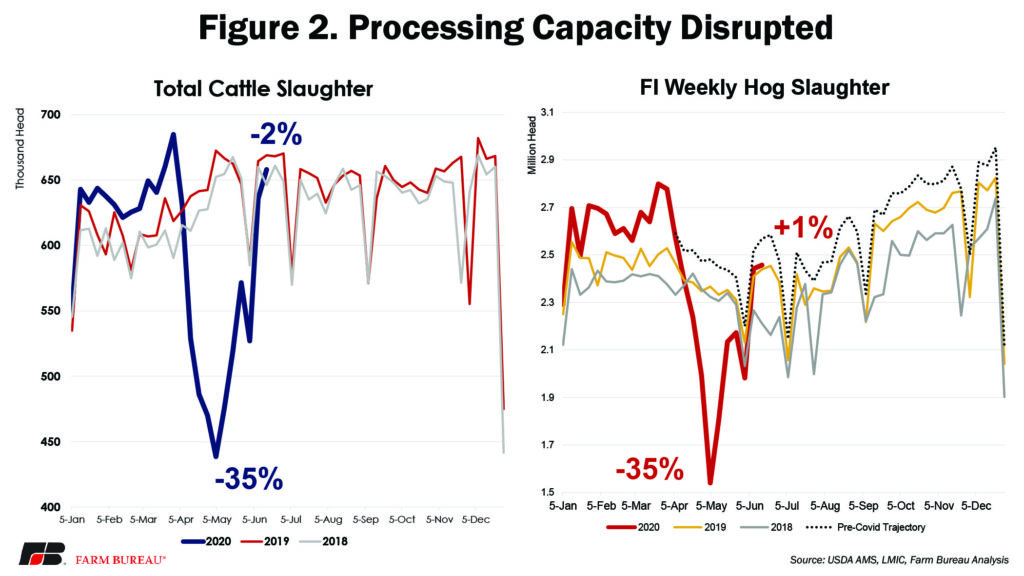

Without the processing capacity, plants could not take delivery of animals, which drove down prices paid to producers and created backlogs throughout the system. Figure 3 (below) shows the dramatic decline in live cattle futures and the roller coaster that lean hog futures have been on.

Pressures on the demand side of the equation

With limited processing capacity comes lower output of meat and poultry products, which has pushed wholesale prices way up.

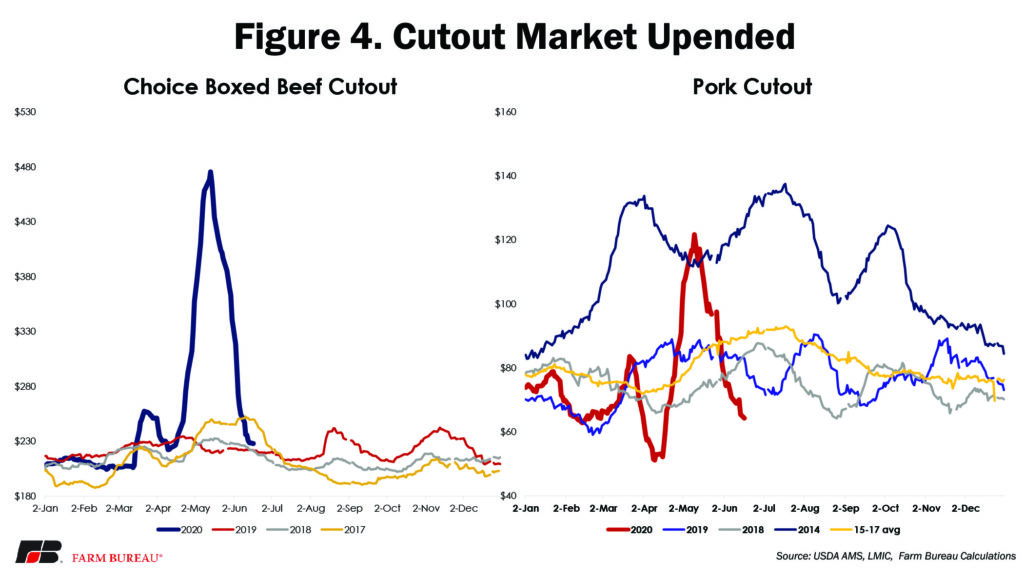

The choice boxed beef cutout has surged well beyond historical levels, more than doubling in value in a matter of weeks. The composite boxed beef cutout increased by 132% from its February low to its May high.

The pork cutout also more than doubled, but for the most part remained below 2014 highs, when PEDv decimated the country’s pork industry.

Something that should be mentioned here is the way beef is sold. On a typical day, a retailer is not going to be able to order more meat for delivery the next day; that is not how the system works.

The meat that retailers sell on a typical day is product the retailer started planning sales around as many as three months before. The retailer may have actually purchased the product as many as six weeks prior. This means there is not a large volume of “unspoken for” meat in the market on a typical day, and much of the meat being processed in a plant has already been sold to a retailer.

The spike in the cutout was partly driven by a surge in demand as retailers looked to refill their meat cases, increasing competition for the small share of “unspoken for” meat.

As processing facilities faced labor struggles and a real strain on supply developed, there was less and less available meat on the spot market, further driving the spike in price.

Because much of the meat delivered to grocery stores during these weeks had been sold to retailers weeks or months earlier, less of it was valued at these historic cutout prices than some think.

Putting supply and demand together

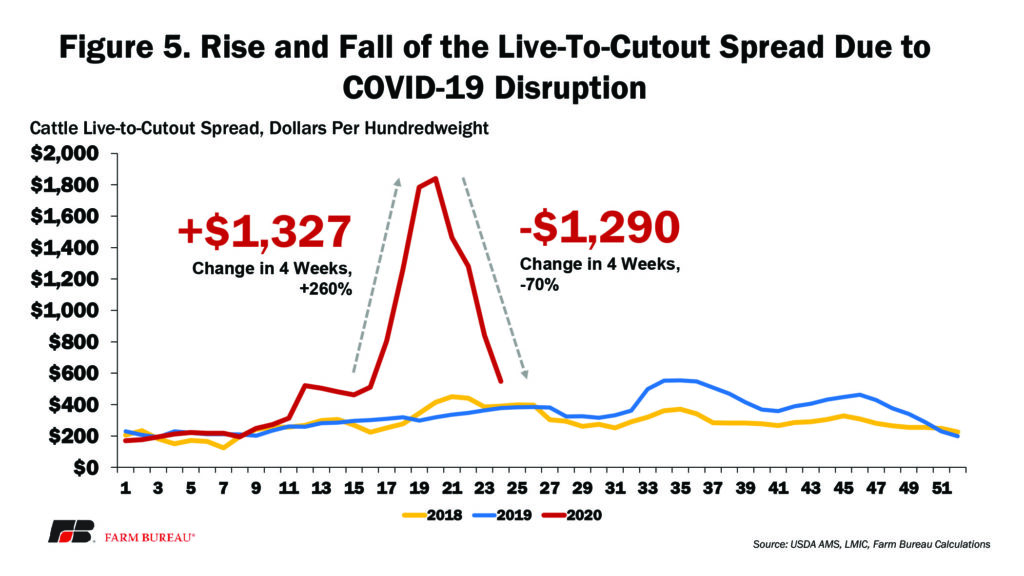

As wholesale prices for meat skyrocketed and livestock prices plummeted, the live-to-cutout spread for beef widened to the degree it caught President

Trump’s eye.

Figure 5 (opposite page) shows the increase in the live-to-cutout spread for beef. This spread comes from the Livestock Marketing Information Center’s database of calculated gross margins on a 1,000 lbs.-of-steer basis.

These calculations are essentially the spread between inputs and outputs and do not include processing costs (energy, labor, etc.) and fixed costs.

It is tempting to look at Figure 5 and draw conclusions about packer margins, but while the live-to-cutout spread typically provides a good measure of the overall health of packer margins, the current environment makes that incredibly difficult to gauge.

Processing plants’ new COVID-19 safety measures add costs that are not included in the spread. There is no way to know those costs without getting a look at the processing companies’ internal information, but one can infer that the cost of protective gear, increased sick leave, increased bonuses and increased incentive pay are very high for these businesses.

Additionally, while a plant may be profitable while operating at 90%-100% capacity, that may not hold true at 50% capacity, even with record-breaking spreads.

The fixed costs associated with operating a plant come in many forms, including massive asset investment costs and large regulatory costs.

The companies normally spread those costs over many animals when operating at or near full capacity, but when capacity is reduced significantly, the ability to operate profitably declines as they spread these fixed costs out over fewer animals.

Taking into account reduced throughput and increased COVID-19-related costs, processor profitability has the potential to decline dramatically.

While there is no way to know for sure how profitable some of these plants are, it is certain that the picture is much murkier than a simple cursory look at Figure 5 would tell you.

The role of international trade

Major disruptions in the cattle and hog markets, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, have led to many conversations about the role of trade for livestock and meat markets.

Export markets offer an important outlet for our product, with exports comprising 11% of beef production, 16% of chicken production and 23% of pork production.

The pork industry in particular made a concerted effort to expand with an eye on export markets as the eventual consumer of that product. In particular, the U.S. has an important trading relationship with our closest neighbors, Canada and Mexico. Over more than two decades, the cattle and hog industries in Canada, the U.S. and Mexico have evolved based on a consistent and favorable market arrangement.

Cattle trade flows play an important role across the U.S. well beyond trade deficits and surpluses, or volumes. They provide numbers to keep feedlots full and packing plants running efficiently. They provide flexibility to adjust to market conditions along the supply chain in all three countries. In turn, these cattle become beef, and free trade agreements allow for our processing sector to ship different cuts to those countries that desire them the most.

The U.S. would be hard-pressed to consume domestically the variety meats from its own cattle supply; these byproducts would otherwise be considered waste without access to other markets that preferred these meats (the typical U.S. consumer isn’t going to be found eating chicken paws, offal and other variety meats found on our animals).

Ultimately, these relationships have increased the value of the carcass in the U.S., finding consumers that value each of these cuts.

Steps taken by AFBF

To capture value for livestock producers, American Farm Bureau is working aggressively, particularly during the coronavirus pandemic, to make sure there is no market manipulation and that livestock producers are fairly compensated for their cattle. To that end, American Farm Bureau:

- Is in the process of convening a working group comprised of state Farm Bureau presidents to investigate the impacts of COVID-19 on livestock markets and actions taken by the packing industry during this crisis;

- Has called for investigations by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and USDA into questionable market practices;

- Has met with both CFTC and USDA officials to convey its strong interest in a robust, aggressive investigation of any market-distorting activities;

- Is supporting the Trump Administration’s initiative to have USDA investigate potential market-distorting tactics;

- Is working with governmental entities and other agricultural organizations to engage in aggressive oversight of cattle markets to ensure producers receive fair value for their livestock;

- Is strongly implementing AFBF policy as written by our producer members to capture fair value for their products; and

- Will oppose efforts that undermine producers’ ability to get the best price for their products.

AFBF’s initiatives are guided by the policies written by our farmer and rancher members. Those policies hold the greatest promise of delivering the most value for producers’ products.